The Collaboration

ATLAS is one of the largest collaborative efforts ever attempted in science.

Organisational Structure

ATLAS is a collaboration of physicists, engineers, technicians, students and support staff from around the world. It is one of the largest collaborative efforts ever attempted in science, with over 5500 members and 3000 scientific authors. The success of ATLAS relies on the close collaboration of research teams located at CERN, and at member universities and laboratories worldwide.

ATLAS elects its leadership and has an organisational structure that allows teams to self-manage, and members to be directly involved in decision-making processes. Scientists usually work in small groups, choosing the research areas and data that interest them most. Any output from the collaboration is shared by all members and is subject to rigorous review and fact-checking processes before results are made public. The success of the collaboration is bound by individual commitment to physics and the prospect of exciting new results that can only be achieved with a complete and coherent collaborative effort.

The only way to realise such a challenging project, with the required intellectual and financial resources, and to maximise its scientific output is through international collaboration. Large project funds are investments from funding agencies of countries participating in ATLAS. There are also contributions from CERN, and some resources from individual universities.

3000

Scientific authors

170+

Institutions

40

Countries

1200

Doctoral students

Caption: ATLAS member countries are shaded blue. Click on country for summary information (double-click to zoom). Orange markers indicate ATLAS institutes (click for information, double-click for zoom). Use mouse wheel or buttons to zoom (click on ocean or non-member area to jump back to world view). See the full list of ATLAS institutions here.

ATLAS Management

The ATLAS management team is responsible for overseeing all the aspects of the collaboration. It is led by a Spokesperson, who has the overall responsibility of the day-to-day organisation of ATLAS. Supporting the Spokesperson is one or two Deputy Spokespersons, whose responsibilities are defined by the Spokesperson. The team also includes a Technical Coordinator, who monitors the overall technical aspects of the experiment; a Resource Coordinator, responsible for the financial and human resources of the collaboration; and an Upgrade Coordinator, responsible for overseeing and monitoring the ATLAS upgrades. The ATLAS Collaboration Board elects its Spokesperson every two years and the position is renewable once (two election terms).

The Physics

ATLAS explores a range of physics topics, with the primary focus of improving our understanding of the fundamental constituents of matter.

What are the basic building blocks of matter?

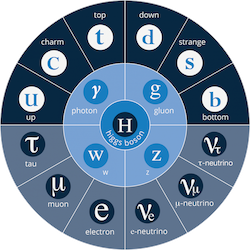

The Standard Model describes the elementary subatomic particles of the universe which have been experimentally seen. ATLAS studies these particles and searches for others to determine if the particles we know are indeed elementary or if they are in fact composed of other more fundamental ones.

What are the forces that govern their interactions?

The Standard Model also describes the fundamental forces of Nature and how they act between fundamental particles. Possible discoveries at the LHC could validate models, such as those incorporating Supersymmetry, where the forces unify at very high energies.

What happened to antimatter?

By searching for imbalances in the production of matter and antimatter, we seek to understand why our universe appears to comprise only matter.

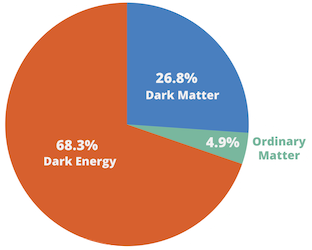

What is “dark matter”?

Astronomical measurements support the existence of matter that cannot be directly seen. The hermetic construction of ATLAS, however, makes it possible to search for this “dark matter”.

What was the early universe like and how will it evolve?

Proton-proton and heavy-ion collisions delivered by the LHC recreate the conditions immediately following the Big Bang when the Universe was governed by high-energy particle physics and later by a primordial soup of quarks and gluons, and allow ATLAS to study fundamental questions such as the Brout-Englert-Higgs field or Dark Matter.

How does gravity fit in?

Gravity is extremely weak when compared to the other forces. To explain the difference we look for such exotic phenomena as extra dimensions, gravitons, and microscopic black holes.

Anything else?

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of the ATLAS physics programme is our ability to explore and discover new phenomena beyond existing theoretical predictions: the search for the unknown.

The Higgs boson

What is the Higgs boson and why does it matter?

Physicists describe particle interactions using the mathematics of field theory, in which forces are carried by intermediate particles called bosons. Photons, for example, are bosons carrying the electromagnetic force. In 1964, the only mathematically consistent theory required bosons to be massless. Yet, experiment showed that the carriers of the weak nuclear interaction – the W and Z bosons – had large masses. To solve this problem, three teams of theorists: Robert Brout and François Englert; Peter Higgs; Gerald Guralnik, Carl Hagen, and Tom Kibble independently proposed a solution now referred to as the Brout-Englert-Higgs (BEH) mechanism.

The ATLAS Experiment

Push the frontiers of knowledge

ATLAS is a general-purpose particle physics experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. It is designed to exploit the full discovery potential of the LHC, pushing the frontiers of scientific knowledge. ATLAS' exploration uses precision measurement to push the frontiers of knowledge by seeking answers to fundamental questions such as: What are the basic building blocks of matter? What are the fundamental forces of nature? What is dark matter made of?

Global Collaboration

ATLAS is a collaboration of physicists, engineers, technicians, students and support staff from around the world. It is one of the largest collaborative efforts ever attempted in science, with over 5500 members and almost 3000 scientific authors. The success of ATLAS relies on the close collaboration of research teams located at CERN, and at member universities and laboratories worldwide.

Experimental behemoth

ATLAS is the largest detector ever constructed for a particle collider: 46 metres long and 25 metres in diameter. Its construction pushed the limits of existing technology. ATLAS is designed to record the high-energy particle collisions of the LHC, which take place at a rate of over a billion interactions per second in the centre of the detector. More than 100 million sensitive electronics channels are used to record the particles produced by the collisions, which are then analysed by ATLAS scientists.

Understanding the Universe

ATLAS physicists are studying the fundamental constituents of matter to better understand the rules behind their interactions. Their research has lead to ground-breaking discoveries, such as that of the Higgs boson. The years ahead will be exciting as ATLAS takes experimental physics into unexplored territories – searching for new processes and particles that could change our understanding of energy and matter.

ATLAS Across Time

The approval of the ATLAS Experiment was an important milestone in the history of particle physics – but it was just the first step in a long journey. Making ATLAS a reality required years of innovative developments in technology and physics. Learn the history of its development in the timeline below.

News from LHCP2019

ATLAS presents new searches for electroweak supersymmetry using the full Run 2 dataset.

Detector & Technology

The largest volume detector ever constructed for a particle collider, ATLAS has the dimensions of a cylinder, 46m long, 25m in diameter, and sits in a cavern100m below ground. The ATLAS detector weighs 7,000 tonnes, similar to the weight of the Eiffel Tower.

The detector itself is a many-layered instrument designed to detect some of the tiniest yet most energetic particles ever created on earth. It consists of six different detecting subsystems wrapped concentrically in layers around the collision point to record the trajectory, momentum, and energy of particles, allowing them to be individually identified and measured. A huge magnet system bends the paths of the charged particles so that their momenta can be measured as precisely as possible.

Beams of particles travelling at energies up to seven trillion electron-volts, or speeds up to 99.999999% that of light, from the LHC collide at the centre of the ATLAS detector producing collision debris in the form of new particles which fly out in all directions. Over a billion particle interactions take place in the ATLAS detector every second, a data rate equivalent to 20 simultaneous telephone conversations held by every person on the earth. Only one in a million collisions are flagged as potentially interesting and recorded for further study. The detector tracks and identifies particles to investigate a wide range of physics, from the study of the Higgs boson and top quark to the search for extra dimensions and particles that could make up dark matter.

Take a virtual walk around the ATLAS Detector in the cavern at Point 1 of the LHC.

iunihnh . gjhbjhbj . hhbjbj

The inner detector is the first part of ATLAS to see the decay products of the collisions, so it is very compact and highly sensitive. It consists of three different systems of sensors all immersed in a magnetic field parallel to the beam axis. The Inner Detector measures the direction, momentum, and charge of electrically-charged particles produced in each proton-proton collision.

Inner Detector

The inner detector is the first part of ATLAS to see the decay products of the collisions, so it is very compact and highly sensitive. It consists of three different systems of sensors all immersed in a magnetic field parallel to the beam axis. The Inner Detector measures the direction, momentum, and charge of electrically-charged particles produced in each proton-proton collision.

The main components of the Inner Detector are: Pixel Detector, Semiconductor Tracker (SCT), and Transition Radiation Tracker (TRT).

Sounds!

Inspired by ATLAS’ optical metrology technology, a team of researchers developed a new system to recover sound from old records.

In ATLAS’ SemiConductor Tracker there are 16,000 carefully aligned silicon detectors. Their accurate position was obtained thanks to optical metrology tools, which can give measurements with a precision of a few micrometres.

Sounds!

Inspired by ATLAS’ optical metrology technology, a team of researchers developed a new system to recover sound from old records.

In ATLAS’ SemiConductor Tracker there are 16,000 carefully aligned silicon detectors. Their accurate position was obtained thanks to optical metrology tools, which can give measurements with a precision of a few micrometres.

Sounds!

Inspired by ATLAS’ optical metrology technology, a team of researchers developed a new system to recover sound from old records.

In ATLAS’ SemiConductor Tracker there are 16,000 carefully aligned silicon detectors. Their accurate position was obtained thanks to optical metrology tools, which can give measurements with a precision of a few micrometres.

text

testt

testtt

testttt

1236

Title Text comp

The Standard Model also describes the fundamental forces of Nature and how they act between fundamental particles. Possible discoveries at the LHC could validate models, such as those incorporating Supersymmetry, where the forces unify at very high energies.

17th March 2019

ATLAS observes light scattering off light

Light-by-light scattering is a very rare phenomenon in which two photons – or particles of light – interact.

27th February 2019

ATLAS releases first result with full Run 2 dataset

The new ATLAS analysis searches for new heavy particles.